March 11, 2024

Peripheral Visions: Poet Laureate

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 16 MIN.

Peripheral Visions: They coalesce in the soft blur of darkest shadows and take shape in the corner of your eye. But you won't see them coming... until it's too late.

Poet Laureate

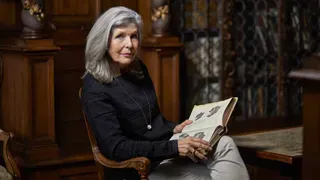

Robert Osunsanmi – "Ossu" to his friends, family, and worldwide legions of fans – sat with an antique ink pen in his hand, the tip poised over a sheet of blank white paper – the real thing, made from wood pulp, and very expensive. He waited. The pen's tip trembled.

He was relaxed and yet alert. He was poised and yet still. He was... waiting. Waiting for the images to come, and the words to follow.

His poise collapsed and he slumped in the chair, feeling exhausted. "No," he chided himself, "the image of a river is too stale, too trite." He did like the idea of drawing closer to a waterfall, it's rumble growing louder to the ear, though...

Ossu wrestled with the notion, then sighed again and put his pen down. "If I only had three or four more decades," he said aloud.

Indeed, if the theists hadn't won the election in '47 and then outlawed most advanced medical treatments, he might have had those extra decades. As it was, human lifespans had shrunk considerably compared to what they had once been. Ossu's father and mother had lived to be 134 and 140, respectively; as a young man he'd felt he had a luxury of time, a century and a half to look forward to if not longer. He had reveled in that luxury. Poetry was a fickle art form. It took a lot of feeding, a lot of gestation, a lot of gentle coaxing... and a lot of time.

The theists' highly controlling regime had upended Ossu's life and plans. He'd only been in his thirties when they came to power, but he knew already that he would be lucky to accomplish even a fraction of what he'd intended if he was going to be forced to live a mere sixty or seventy years – maybe a little longer, though that was rare, lingering environmental toxicity being what it was.

There was an upside in that his work had taken on a new, compelling urgency, and the urgency had fueled his intense work ethic in the decades since. Now, on the verge of reaching his sixtieth year, Ossu was feeling the press of time more acutely than ever before. He was also feeling insufficient to the task of crystallizing his thoughts and feelings, much less formalizing them in verse.

Ossue stared at the blank page and felt a hatred for it he'd hardly ever felt in his life. Words had always come easily to him. Not now, though – not now that he was feeling like he might have one last major work in him, but not enough strength or time to realize it.

The late afternoon sun seeped into his study as he sat at his desk, staring at the page, mulling analogies, word choices, and rhythm schemes.

All I need to do is tell the truth, he thought. That was how he'd written all his work: By stripping away cleverness, obfuscation, and ego. Once he let go of fear and expectation, the work almost wrote itself... if he had a solid grasp of a theme, that was.

Maybe that was the problem. Maybe he didn't really know his theme. His subject was mortality, but that was a vast and complicated thing to ponder. Should he focus on his life's joys? Its regrets? Should he revisit the so-called Big Questions that he felt he'd pinned down, or attempt to address the ones that remained out of reach?

The truth... the truth is I'm feeling tired and wrung out, my words all used up.

Ossu sat back in his chair. The blue robe he wore over his white tunic shifted and flowed with a faint rustling sound.

The poet stared at the page as the light grew golden, then orange, and then he felt his weariness taking him over. He set his pen aside and rested his head on folded arms.

"The urge to live is universal," a voice said.

Ossu jolted awake. The room was dark, except where silver moonlight streamed in through the window.

"Who's here?" Ossu asked, looking around. He waved a hand to signal the lights to come up, and they did.

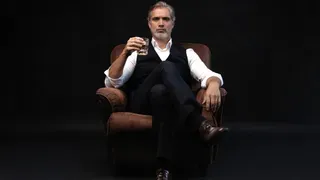

A man sat in one of the chairs by the bookcase across the room.

"Who are you?" Ossu asked. "Did my wife or one of my children let you in?"

"No, Mr. Osunsanmi, they did not. They shouldn't know I'm here. Not until after we've had a chance to talk."

"Why? Are you... are you from the Religious Police?" Ossu kept his voice steady but felt a shudder of anxiety. There was no such thing as privacy, private property, or personal rights where the Religious Police were concerned. He knew he should have no reason to fear them; one of the reasons he was so widely read and so celebrated was his ability to merge beauty and truth with just enough of a polish of dogmatic nonsense that the Religious Police and other moral authorities were content to let him work unmolested.

But maybe something had changed? A spiritual directive might have been reinterpreted, or a word's definition might have been changed by the one or another of the political and cultural committees, retroactively transforming an innocuous verse from years ago into something dangerous, treasonous, or even blasphemous...

"Calm yourself," the man said. "I'm not from any earthly authority."

"Do you mean – ?" Ossu couldn't finish the sentence. He'd never given any outward suggestion of it, but had he ever been subjected to a thought probe he would instantly have been revealed to be an atheist – the worst thing one could be in their society, other than a homosexual.

But what if he'd been wrong? What if the godly and infernal forces to which the theists ascribed every force in nature, every outcome, and every human deed were real? What if he were in the presence of an angel... or even one of the gods...?

Ossu, unable to say the words, simply pointed upwards.

The man laughed.

"If you're asking me whether I'm from the space station, then yes. I am."

Ossu stared at him, stunned. At the same time, the man's words made everything make sense.

"The space station?" Ossu asked. "You're one of the people up on the hill?"

That was the euphemism people used now to refer to the space station and its permanent residents. In many ways, anything having to do with science, including space travel, was tricky to discuss. One couldn't openly embrace the ideas of cosmology that the fallen civilizations had believed in, with skeins of galaxies distributed in an infinite volume of space, a universe expanding and evolving across an eternal stretch of time. So-called standard technology was still used, of course – even the religious elite enjoyed the conveniences of electricity, transportation, and basic medicine, to say nothing of scientifically efficient food production; then, too, the government found the use of personal communications devices, home computers and reading slates far too useful for tracing the movements and thoughts of its subjects to dispense with such devices. But in no way was it wise to suggest scientific facts should be prioritized over religious sentiments, either in social life or affairs of state.

The people up on the hill, though... they were beyond the reach of the theist government, either the one here at home or the others around the world.

The people up on the hill had left Earth for good more than a century and a half ago, in order, they said, to live a life or peace, order, and reason. Such was a necessity when living on board a space station. Nether simple faith nor endless prayer was a substitute for the hard work and the mental rigor demanded by the task of survival in the airless void above the blue of the daytime sky. If the people up on the hill believed in the gods, then they were versions of the gods that required self-sufficiency, a lack of ego, and a willingness to learn about the mathematical and physical nuances of the real world.

In a way, the people up on the hill were more frightening than the gods. They were said to possess machines that could do anything; some even said that the people up on the hill had become machines, forsaking their human flesh and their living souls in the process.

But the man sitting in Ossu's office didn't look or speak like a machine. He seemed perfectly human.

"Are you real?" Ossu asked.

"Do you mean to ask if you're dreaming? No, you're wide awake and I'm paying you a visit. Do you mean to ask if I am physically in the room with you? No, I'm afraid not. This is a kind of projection. I'm on the space station, which at the moment is directly overhead from your position on the Earth. The station moves across the sky from your point of view; I'll be able to converse with you for about half an hour, until the station crosses the horizon and we lose the line-of-sight transmission window."

"I don't understand," Ossu said.

"Then don't worry about it. Just know that I have a reason for being here, and our time is limited. I hate to rush you, but you're required to make a decision."

"About what?"

"About your future... and your past."

"I don't..."

"Yes, you're right, I should speak plainly and leave the poetry to you." The man smiled. "But it's going to be difficult for you to comprehend. So, let's try this: Don't try to understand it, at least not right now. Just hear the general proposal I mean to make you and then answer me at once."

"Answer...?"

"Hear my explanation, then my proposal."

"All right," Ossu said.

"You, Robert Abayomrunkoje Osunsanmi, have been named prospective Poet Laureate by those of us who live on the space station."

"Poet Laureate?"

"It's a distinction we bestow once every forty-two years – literally once a generation. We choose our poet laureate from among candidates all over the Earth."

"I never heard of this..."

"No one from this country has bene chosen before. And also, the last time we chose a poet laureate – the last time we interacted with anyone from your country – was before the current regime came to power. I'm guessing they would never have allowed you to hear about it even if we had chosen one of your countrymen earlier in their reign."

"No... probably not," Ossu said.

"In case you are worried about the religious authorities punishing you for the fact that I am sitting in your study... well, I'm actually not, but I am communicating with you... I should tell you up front that they won't ever know. Especially not if you choose to accept the award that comes with the title."

"The title?"

"Poet Laureate."

"Yes, of course," Ossu said. Then, still feeling like he was trying to catch up, he said: "There's a prize? Is it money?"

"Not hardly. Any material reward would come to the attention of your government, and knowing what assholes they are, they'd probably execute you and your entire family simply for hearing me out."

"I'm certain they would," Ossu said, thinking he should be terrified but not feeling so much apprehension as curiosity. "What is it you are offering?"

"Traditionally, we offer our poet laureates the thing they most want, assuming it's within our power. There have been three poet laureates before you; in each case, we were able to grant their fondest wish."

"Like a genie from the old stories," Ossu smiled.

"Like advanced, sane people who understand the proper uses of science and the possibilities offered by a willingness to learn the secrets of the universe as it actually is, rather than clinging to mythologies that make no sense." The man's voice was a little harsh and a little heated, but he was smiling back at Ossu. "All which is to say, we can give you what you most want, as we did for those who won the prize before you."

"You sound very confident, but how do you know you can give me what I want?" Ossu asked.

"Because we already know what that is."

"What... how? How can you know something like that?"

The man shifted in the chair, seeming to sit forward, his body language suggesting happy excitement. Ossu could see that he was bursting to share what he had to say.

"We know because we have read your poetry. All of your poetry – including what you're working on now. The poem you have been composing in fits and starts for two years."

"You've spied on my private papers?"

"No, your government did that. We simply accessed your government's data files on you, including your work – all of your work. Everything you've ever written: Published, discarded, abandoned, and in progress, all your work. They have all of it."

"But... how? I use pen and paper for the simple reason – "

"Yes, 'pen and paper can't be hacked.' We've heard this before. But the truth it, pens can be hacked. If you know how to look for it, you'll find a tiny geosensor embedded in your pen. It tracks the movements of the pen as you're writing, and a monitoring program reconstructs whatever it is you're putting onto the page. That script is automatically converted into text, and that text goes into your personal file in the governmental database, all in real time."

Ossu frowned, each word heightening his anger.

"I see this has upset you. I don't blame you," the man said, "but did you expect anything different?"

Ossu looked at his desk, at the offending pen. His trusted pen... his enemy.

"No," he said. "At least, I shouldn't have."

"Well, don't worry that our conversation will also be observed and recorded," the man told him. "We have neutralized the monitoring devices the state placed in this room. All they will see or hear of this room for the next..." The man closed his eyes momentarily, as if checking. "...twenty-four minutes is darkness and moonlight, and you asleep at hour desk."

This was all very interesting, but Ossu was getting tired of it. "What do you want?" he asked.

"It's more a matter of what you want," the man told him. "Which, from our analysis of your writings, comes to this: You want to live. That's not so hard to guess, really, since all living beings, generally speaking, want to keep living."

"So you said," Ossu replied, thinking back to the words that had woken him up for this strange conversation. Or was it a dream? The man had it was not, but could he trust the words of a dream that told him it was not a dream?

That, he thought, might make for an amusing short poem. Or perhaps not... if the government divines the reason for its being written.

"More specific to you – you want to be able to keep writing poetry," the man said. "And, no offense, but I think you would agree that your finest work was written in your younger years. I think what you really want isn't to keep living and aging while you write, but to be young again... young and sharp and inspired and, more to the point, at the start of your career."

Ossu scoffed. "That can't happen. One lives one's life only once. Or do you mean to give me some sort of youth serum? That certainly would attract unwanted attention from the moral authorities."

"Yes," the man said, fairly sparkling with glee. "But that's not what I mean. Yes, you have a single life to live, and you are drawing near the end of that life. It must be frightening, and it must puzzle you. How did so much time go by? How did you really do all that work already?"

"It... it does feel that way," Ossu said.

"As I mentioned, we can understand some things because they are universal. And the rest, the specifics, we have gained a sense for by reading your work. It's been that deep, considered reading that decided us to name you our poet laureate, by the way. We have deeply read and considered... and debated and defended.... hundreds of other poets on Earth, but you emerged the clear winner in the end."

"Why?"

"Your poetry is simply the best. And, like you, we are certain you would write even more stirring, lovely poetry if you had the time for it."

"But how can you give me that time? It simply isn't possible..."

"Of course it is, or we wouldn't offer it to you. I'll explain this simply: We can project your mind as it is right now – this very moment – back into your own younger self, decades ago. You'd have your whole life to live over again. But you would also have your life experience as you have accrued it – your wisdom and your insights and your world view."

"My memories," Ossu said.

"More than memories," the man told him. "Your sensibilities. Your convictions – your values."

Ossu nodded. "Yes. Poetry is nothing without values..."

"It might be words, it might be verse," the man agreed, "but it certainly is not poetry without a strong sense of personal values."

"And what would happen then?"

"You would live the life we made possible for you. A new life."

"Wouldn't I simply repeat what I have already done?" Ossu shuddered. "That would be amusing, perhaps, in places, but also a torment."

"No," the man said. "You would be free to make different choices. Marry someone else. Or seek a marriage exemption: Tell them that you need to focus on your work, you need to commit yourself entirely to your spiritual journey. Become a cleric, claim that celibacy is part of your spiritual path. You're not a worker or a soldier, so procreation is not an absolute mandate for you. You do have a little freedom even in this horrifying regime."

"But then my... my children..."

The man nodded. "Yes. I'm afraid this gift does entail sacrifice. Your children would never be born. But we believe in a person's right to choose their destiny, and all that such choices entail. We can't offer this sort of freedom to everyone – but we do offer them to a select few."

Ossu hesitated. "They're my children," he said. "I wouldn't want them not to be born."

"If you really wanted, you could marry the same woman. You could try to have the same children – though honestly, the odds are very much against it. But you could have some children, even if they were different from the ones you have now. And you could have thirty or forty years more to write, depending on the date in the past to which your mind was projected."

"What would happen to who I was back then?"

"He would be replaced by who you are now."

"Isn't that some sort of paradox?"

"No."

"But..."

"Please, Ossu, don't try to tell us our business. We're scientists. We have done this before. We will do it again."

"But... if I make different choices, the world will be different. You will be different. You, as you are now, will no longer exist. It will be a kind of death for you."

"Like I said, don't try to tell us our business. We will be fine, I promise you."

"What about my work?" Ossu asked.

"It will be erased, of course," the man said. "You might re-write some of what you've already composed, but it won't be the same. How could it be? You won't be the same. Your new work will, however, be more skillful, richer, more elegant... as you will be."

"My work," Ossu said. "My work will be erased."

"That's what I'm telling you," the man said. "But you'll write better work to replace it with."

"Will I?"

"Don't you have faith that you will?"

Faith. Ossu felt the word ring in his mind. He'd spend his life hearing about the necessity of faith, the moral primacy of faith, the insistence from the powers that be that the obvious cruelty and corruption in the affairs of state were all part of the will of the gods; the people simply needed to have faith...

It was all a lie, and if the gods even existed then surely they damned this so-called "faith" in no uncertain terms.

Would this be any different?

They sat in silence for a long while. Finally, the man said: "Our window of opportunity is closing. I won't be coming back here, so tell me now. Do you wish to be our poet laureate and accept the prize that comes with it: The chance to live your life over again, just as you've been yearning to do?"

***

His children – Corrine, Alexander, and Matteo – gathered around him in the family sitting room, and his wife sitting at his side, Ossu explained as best he could about the offer that had been made to him.

The man had assured him that the monitoring devices in the living room would show the government nothing of the family meeting. Still, Ossu cautioned his family against saying anything to anyone – ever – about what he was going to tell them. They all nodded. They all had some level of piety inculcated into them – Alexander was the least religious, but even he had absorbed some of what the theists wanted all the citizens to believe – but they weren't stupid. They knew their government was corrupt and their church stood between themselves and God rather than serving as a bridge to the divine.

As concisely as he could (and, being a poet, he could make himself understood with few words), Ossu explained what had happened.

"Will you accept?" Corrine asked him.

"To have accepted would mean I'd not be here right now. I would be gone. Or, even if I existed in this moment, having lived the last thirty or forty years again, none of you would be here. Others might be..." He glanced at his wife. "Except for you, my love. But probably not the rest of you."

"So..." Matteo frowned, trying to comprehend it. "So, you said no?"

"Well, obviously, I declined," Ossu told his son. Looking around at his family, Ossu was about to explain why, when Corrine leapt to her feet, rushed over, and threw her arms around him.

"Papa!" she exclaimed. "It's for us, isn't it, that you sacrificed the opportunity to be young again, to write as you once did... that you forsook the time to complete your next great work!"

"Ah..." Ossu hesitated, then smiled at her. "Go on, my pet," he encouraged her.

"We always talked among ourselves, my brothers and I, about how distant you seemed... always wrapped up in yourself, in your words, and so impenetrable to us," Corrine said joyously. "Your feelings were always meters and syllables, never a hug or a kiss. But you do love us! You do! And this proves it."

Corrine's words unleashed a storm of love and joy. Laughing and sobbing, his sons drew closer, too, and embraced him in a tangle of arms. Above their exclamations Ossu saw his wife's eyes glowing at him with love and pride.

My family, he thought. How could he tell them the truth? He'd been about it, but now.... now he never could, understanding their feelings and their point of view.

It had not been the thought that his children would disappear, never having been born, that had stopped him from accepting the offer. It hadn't been the thought that he and Fowoke might never marry that had made him choose the life he'd lived... a life nearly over... instead of a chance to do everything afresh.

It had been his work. He could not bear the thought of his work being erased, written over, undone. Even if it were to be replaced with new, and perhaps superior, work, he couldn't forsake the words he had written, the children of his soul and his mind.

They had been his life, his work, and his meaning. That could never be replaced, not even with new poetry.

Ossu smiled, and laughed tenderly, and stroked his children's backs and heads and told them that he loved them. And he did; that was why he didn't tell them more.

Because, he thought to himself, more than a theme or analogy, more than any brilliant string of words, a poet must know where to let silence lie, and where to let a verse conclude.

The moment was here; the moment was now. As the man from among the people up on the hill had told him, tonight would be the last night of his life.

His life, the life he had wrought, every syllable carefully considered and chosen.

His life to the end.

Next week we train our eyes on the choices a man named Bec makes when he's presented with a vision of loveliness far more appealing than what he already has in his life – only to learn that there's a place, lovely and yet limited, for "Grace."

Kilian Melloy serves as EDGE Media Network's Associate Arts Editor and Staff Contributor. His professional memberships include the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the Boston Online Film Critics Association, The Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, and the Boston Theater Critics Association's Elliot Norton Awards Committee.