October 4, 2017

California Plans on Teaching LGBT History in Schools

Colton Wooten READ TIME: 1 MIN.

California begins to choose which textbooks it will draw material for new curricula after becoming the first state to ever adopt LGBT history guidelines.

So far, twelve textbooks are being considered. But many of them may be rejected.

Our Family Coalition and Equality California met with the Instructional Quality Commission and suggested the IQC reject all but two of the twelve textbooks and include various degrees of changes.

"We had historical figures that actually had same-sex relationships and contributed in positive ways," Executive Director of OFC Renata Moreira said according to Gay Star News.

The state introduced the FAIR Education Act in 2011, which provided that state schools would teach LGBT history. The act requires that school systems update their teaching rubrics and textbooks their anthologies to include certain historical events from LGBT history that have been ignored otherwise or broached only in part.

"The California Education Code has been updated over time to make sure that the role and contributions of members of underrepresented racial, ethnic and cultural groups to the economic, political, and social development of California and the United States are included in history and social studies lessons," reads the act's website.

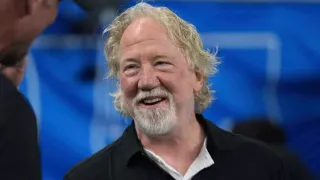

Mark Leno, the former Democratic senator and author of the bill itself, said of the law's aspirations:

"The historically inaccurate exclusion of LGBT Americans in social sciences instruction as well as the spreading of negative stereotypes in school activities sustains an environment of discrimination and bias in school throughout California."

Copyright South Florida Gay News. For more articles, visit

Copyright South Florida Gay News. For more articles, visit